The Collected Works of Arthur C. Clarke

Clarke's "2001" may be a snooze-fest, but it revolutionized sci-fi cinema. His real genius? Short stories that predicted everything from social media chaos to internet porn. While AI may have gotten HAL's paranoia right, we traded Clarke's hopeful space-faring future for division and doom-scrolling.

2001: A Space Odyssey* was boring. There, I said it. I know you were thinking it. After the chimpanzees smash bones, to Thus Spoke Zarathustra, there are about a hundred minutes of nothing until we get to, "Open the pod bay doors," followed by a light show that requires the high of psychedelics to appreciate.

That 2001 was boring did not stop it from becoming the most influential film made in my lifetime. The accurate (1968 accurate) depiction of space flight with ships matching rotation and a Pan Am flight attendant clomping along in gravity boots was a needed reality check to Star Trek's Enterprise and Lost in Space's Styrofoam sets.

Whenever my monopoly-controlled internet connection fails, and Alexa cannot turn off my bedroom lights or tell me the time, I am reminded of Arthur C. Clarke's vision and that glowing eye of Hal. (Hal is not a Wake Word for Alexa because the false positives generated by a single syllable sound).

(Douglas Rain, the voice of HAL, died on the day I started writing this post. Like Arthur C. Clarke, his best work was not 2001: A Space Odyssey. For 32 seasons, Douglas Rain played Shakespeare's most intriguing and iconic characters for the Stratford Festival).

As mind-numbingly dull as 2001 is, it was not Clarke's dullest work. The award-winning Rendezvous with Rama takes that prize. I tried reading Rendezvous with Rama when I was in college; it put me to sleep every session. Half the pages on that old paperback were folded over from me rolling on top of it in the middle of a nap.

The problem with both works is in the details. The excruciating details that made them groundbreaking, award-winning works of science fiction contributed to the modern blockbuster. Every mad computer—even Lost In Space's ROBOT—inherited HAL's certainty that it knew better.

Clarke's influence reaches beyond fiction; every chuckle at last week’s claim by a Harvard astrophysicist that Oumuamua was an alien spacecraft was born in Clarke's Rendezvous with Rama. Rama was a cigar-shaped object from interstellar space, traveling at impossible speed.

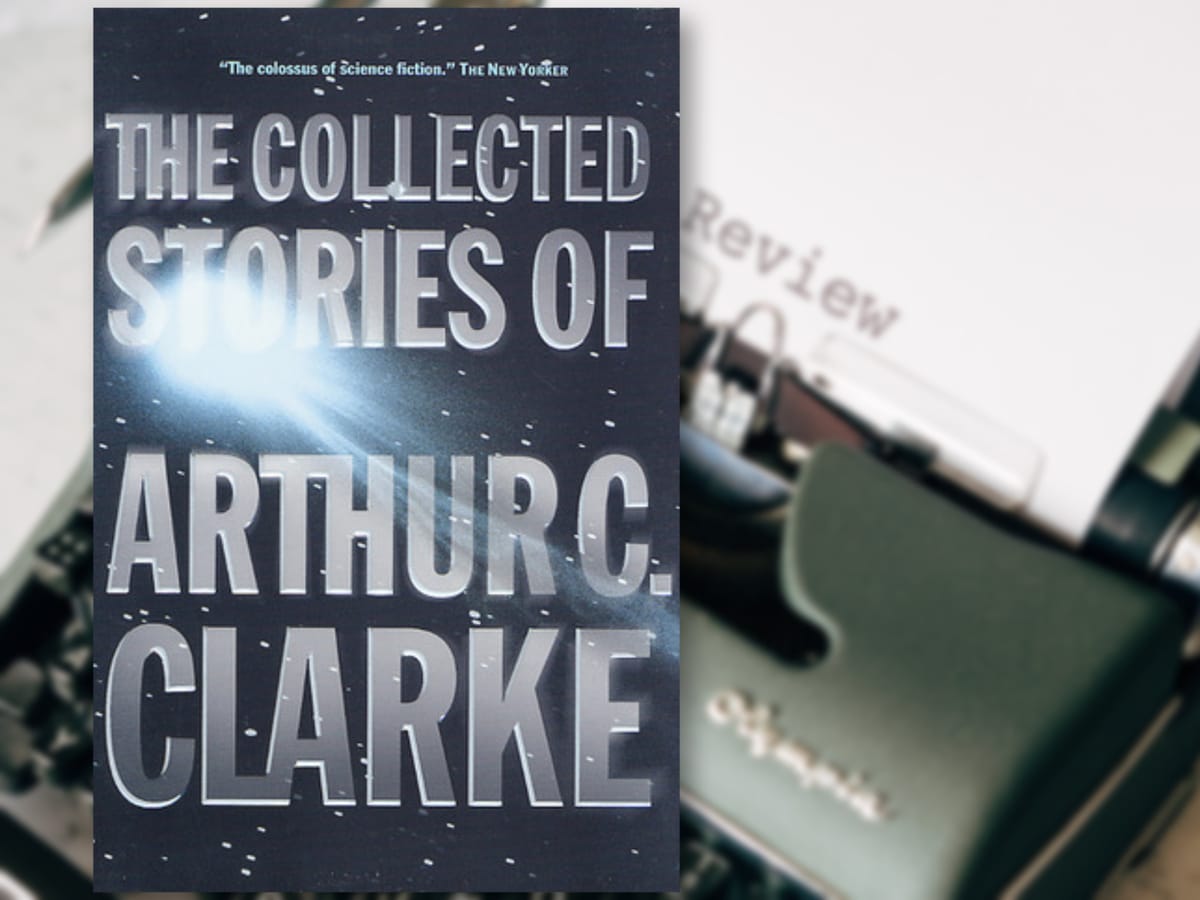

While Arthur C. Clarke's novels have had an oversized impact on science and science fiction, it was his short stories that most influenced me. When forced to count his words, Clarke did his best work. You can find almost all of them in The Collected Stories of Arthur C. Clarke.

Here is the genesis of everything dull. The Sentinel became 2001: A Space Odyssey, but—limited by column length—makes its point without the exposition and accuracies of space travel. Star Trek's teleporter was a human telegram in 1937's Travel By Wire. Aliens living as humans and influencing, or abandoning, our civilization was 1938's Retreat from Earth.

As early as 1939, Clarke speculated that all the ideas for science fiction had been used up and shared his division of science fiction from fantasy. In the following decades, he proves himself wrong on the first part and horrifying correct on the second with stories like Whaky, Technical Error, Loophole, and Castaway. From the distant future, Venusians visit our world to learn how we lived through archeology. Their conclusions are surely as wrong as ours are about past human civilizations.

While The Sentinel gets most of the credit for 2001, other stories contributed to the groundbreaking snore-fest. Breaking Strain is about being trapped in space. It spawned another forgotten work; a movie named Trapped in Space.

If you listen to the Audible version of this book on noise-canceling headphones, you will feel Clarke's prescience while listening to Silence, Please_. In the introduction to Times Arrow, Clarke reminds us how hard it is for a science fiction writer to stay ahead of technological progress. A challenge I have now concluded follows Moore's Law.

Everything here is good, but two stories stand out for me. The first is The Nine Billion Names of God, where a Buddhist monastery requests the aid of a supercomputer to calculate all the names of God. With the job complete, the stars over the Tibetan sky wink out of existence. The other is one that takes on added meaning with each passing decade: I Remember Babylon.

In I Remember Babylon, communists intend to use a communication satellite to broadcast an uncensored mix of pornography, gore, and propaganda into every American household. The plan is to use America's consumerism and amoral capitalist ideals to overthrow the government. Internet porn, social media, fake news, Napster, BitTorrent, newsreaders, and unmoderated comment sections were not on Clarke's radar. In the story, pornography was as modest as the figures on Indian temples engaged in sex acts; acts that OnlyFans models now do in Wal-Mart changing rooms.

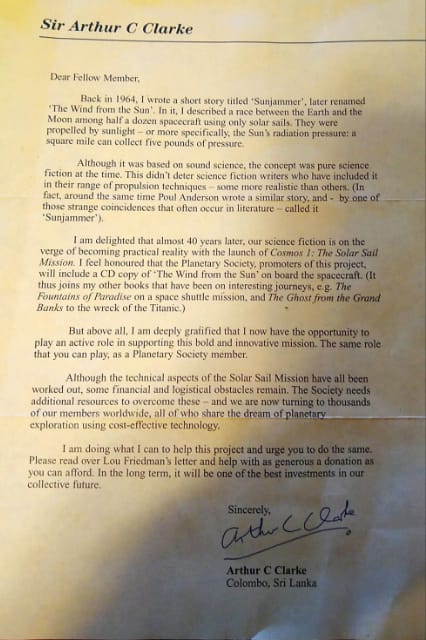

Writing is telepathy over time. Clarke succeeded beyond most of his peers. Clarke's work shaped modern cinema and television. As for Arthur and me, we have another connection through The Planetary Society.

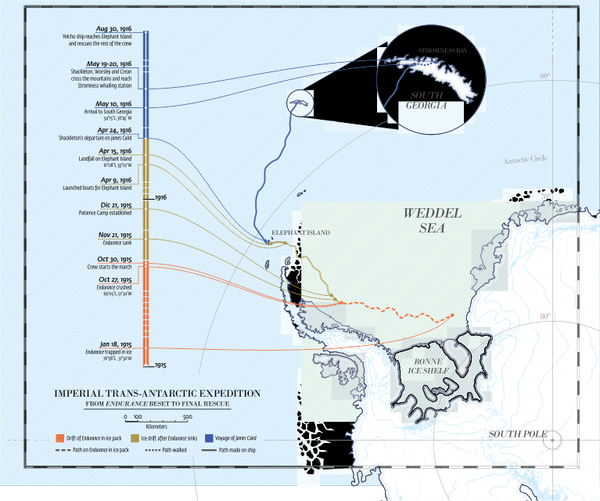

Founded in 1980 by Carl Sagan, Bruce Murray, and Louis Friedman, The Planetary Society is a nonprofit foundation that does actual engineering projects. The biggest of these is Louis Friedman's idea of a solar sail. Named Cosmos 1, the original solar sail project was packaged into a refitted nuclear missile and launched from a submarine in the Barents Sea.

The rocket failed short of the intended orbit. Had it succeeded, Arthur C. Clarke proposed a reverse Babylon project to track the sail's progress. The idea was to create a citizen tracking service using satellite TV dishes to find and track the solar sail's signal from space. That mission failed in 2005, and thirteen years later, the CubeSat version of the sail has yet to reach orbit. In the intervening years, JAXA launched IKAROS (Interplanetary Kite-craft Accelerated by Radiation Of the Sun). This ship solar sailed, but the acceleration was so small as to be negligible.

Before 2001, the year had a singular vision: travel to the outer planets with Pan Am flights to space stations orbiting the Earth. After 2001, we remember the year for a singular horror. That we as a collective species could not come together to create Clarke's vision of 2001 is a singular disappointment. Instead of a future built on science, we have a present poisoned by religion. Instead of a common good, we have endless divisions magnified by the Babylon Projects of 24-hour news, social networks, and political campaigns. Every year across the globe, trillions of credits are spent on sowing division, then profiting from that division with the production and use of weapons. The beginning of this century looks very much like the beginning of the last. Nationalism festers across the globe. Neighbors are intruders if they cannot be profited from, and worse if they cannot support themselves. 2001: A Space Odyssey might have been a boring look at a potential future, but at least it was a hopeful one. There is little of that left in today's fictional or rational realms.